Does Telling Stories Really Make You 22 Times More Memorable?

Think about your favorite movie. What was the name of the main character? What did you like about him or her? What happened to the character throughout the movie? You can probably recall the plot in great detail.

Now think back to the last quarterly update your organization’s leadership sent around internally. Maybe you can recall a statistic or two, but I’ll bet you’d be hard pressed to recount any significant portion of the report to your colleague who hasn’t read it yet.

That’s because there’s no story to tell. No narrative arc, no emotional moments, no suspense, no climax. Just the facts. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

Research shows that messages delivered as stories can be up to 22 times more memorable than just facts.

It’s an oft-cited statistic, and for good reason, even if that multiplier may be a bit hyperbolic. At Quantified Communications, we encourage our clients to incorporate storytelling into every single communication opportunity, from political campaigns to conference keynotes to internal addresses to financial communications.

Your annual investor day may not be feature film material, and your sustainability report may not be the next Great American Novel, but if you wrap your results into short narratives introducing the people behind the initiatives and detailing the efforts that led to your successes (or shortcomings), your audiences will be able to visualize those initiatives and efforts themselves. In turn, they’ll be more likely to remember what you have to say — and they’ll be more likely to perceive you favorably.

What is it about stories that gives content such a boost?

Stories Act as Mnemonic Devices for Facts

Mnemonics work by organizing abstract material into a meaningful structure, using such techniques as imagery, rhyme, or story to make the material easier to learn. Think back to grade school, learning the metric system prefixes. Kilo, hecto, deka, deci, centi, and milli might not have stuck, but “King Henry died drinking chocolate milk” sure did.

In the same way, abstract statistics like, “we reduced manufacturing costs by 32 percent,” may not stick on its own. But when it’s wrapped in a story about why it was important to reduce costs, who came up with the new designs, and how they did it, that data point — and the success it represents — becomes memorable and real.

Stories Engage Our Emotions

Research has shown that audiences are more likely to engage with and adopt messages that make them feel personally involved by triggering an emotional response. And storytelling, with all its excitement and suspense, is a great way to achieve that.

Advertisers know this better than anyone else. The same companies come up with the most memorable Super Bowl commercials year after year. These are the ads we anticipate before the game and share on our Facebook pages afterward. These are the ads that tell stories.

Consider, for example, the Budweiser’s “Lost Dog” ad from Superbowl XLIX, in 2015.

Of course, we’re not saying that every presentation should include puppies — but do consider the power of emotion in crafting memorable, persuasive messages.

Stories Make Us Use Our Brains Differently

Researchers at Ohio State conducted several experiments on cognitive processes that occur when we become immersed in a story. They call that feeling — of being so lost in a narrative that we hardly notice the world around us — transportation. And they discovered that when we’re transported by a narrative — whether it’s true or imagined — we tend to view the protagonist more favorably and embrace the beliefs and worldviews the story presents.

Most importantly, though, we tend to believe the story more readily than we would believe a non-narrative account. This is because our brains actually process narratives differently. When we’re taking in straight information, we’re paying critical attention to the message — reaching back for our own existing knowledge and opinions and actively analyzing what we’re hearing.

When we’re transformed by a narrative, however, our single focus is on the story. We absorb it entirely, without pausing to deconstruct or doubt what we’re hearing. We’re truly swept away, and this makes us more likely to embrace the ideals and messages the story is promoting.

How do you tell a story?

In his recent Politico article on how storytelling decided the 2016 election, Mark McKinnon (of Showtime’s The Circus), outlines it like this:

“Identify a threat and/or an opportunity. Establish victims of the threat or denied opportunity. Suggest villains that impose the threat or deny the opportunity. Propose solutions. Reveal the hero.”

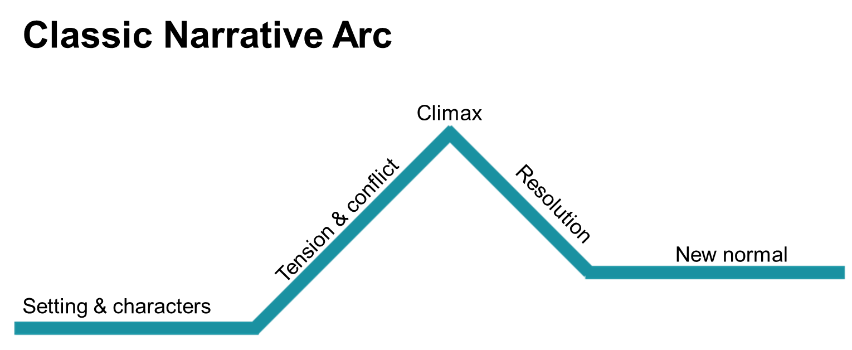

Executive communication coach Briar Goldberg elaborates on McKinnon’s advice, detailing the classic narrative arc she uses to help speakers frame their messages as narratives. The best stories, she says, start by establishing the setting and introducing tension through conflict. The turning point, when the tension is at its highest is the climax, and what follows is the resolution of the conflict, establishing a new normal for the characters.

Think back again to your favorite movie. You should be able to identify each of these moments, and we’re seeing them more and more in our analyses of corporate and executive communication.

Think back again to your favorite movie. You should be able to identify each of these moments, and we’re seeing them more and more in our analyses of corporate and executive communication.

For example, when Tim Cook spoke with Time Magazine this spring about Apple’s privacy conflict with the FBI, he offered the facts about Apple’s stance, but he went deeper than that, sharing the discussions and processes behind the decisions they’d made and the values driving those decisions, all in the context of the timeline of events:

“I think the attack itself happened midweek, Wednesday or Thursday, if I remember correctly, and we didn’t hear anything for a few days. I think it was Saturday before we were contacted. We have a desk, if you will, set up to take requests from government. It’s set up 24/7, not as a result of this. It’s been going for a while. The call came into that desk, and they presented us with a warrant as it relates to this specific phone. […] The warrant was for all information that we had about that phone, and so we passed that information, which for us was a cloud backup on the phone, and some other metadata, if you will, that we would have about the phone. […] Some time passed, quite a bit of time, over a month I believe, and they came back and said we want to get some additional information. And we said well, here’s what we would suggest. […] So we were helping. We were consulting in addition to passing the information that we had on the phone, which was all the information that we had. Some more time passed, and they started talking to us about how they might sue, or they may put a claim in. But they never told us whether they were going to do it or not. By then it’s seventy-five days or so from the attack.”

The characters are Apple and the FBI; the setting, the lone government phone desk. The tension begins to build as the FBI requests more and more information from Apple. And this is only the beginning of the interview. Cook continues, reliving the entire series of events, turning the incident from a “he said/she said” situation into a true narrative that the audience can watch as it plays out in their mind’s eye. As a result, readers are likely more inclined to view Cook and his company favorably, and to recall the salient points from the interview.

At Quantified Communications, we help our clients bring their companies’ stories to life through this kind of sensory, emotionally oriented language that keeps audiences invested in the material. It’s this kind of language that makes listeners relive a presentation in the breakroom later that week, or share its key moments with their family at the dinner table.

To find out how QC can use our communication analytics platform to help your leadership deliver best-in-class messaging, email us at info@quantifiedcommunications.com.