Which Candidate is Using Narrative to Get Ahead?

All About Storytelling in a Political Game.

Think back to our most recent presidents. What do you recall about their campaigns? How did they win our nation’s votes? Was it their policies? Their parties? Their commercials?

According to Mark McKinnon, chief strategy and media advisor to a former US president, and producer of the Showtime hit “The Circus,” it was their stories.

McKinnon says that when it comes to political communication these days, we tend to favor the presidential candidate who comes with the best narrative.

We vote because of the story.

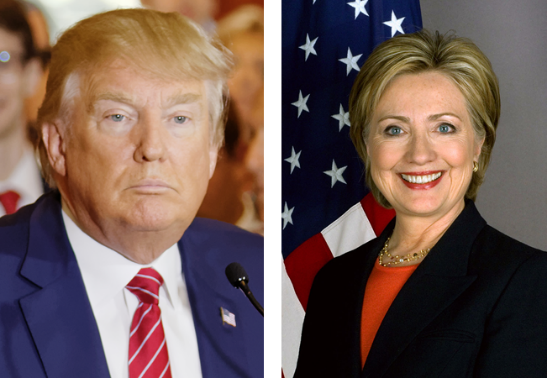

As the 2016 election ramps up, with Republican and Democratic National Conventions just around the corner, the GOP nominee is certainly selling a story — America is falling apart and he can make it great again. Hillary Clinton, however, is a little more complicated. She presents differently one-on-one than she does in front of a crowd, keeping her private life separate from her public one, and juggling a long history of personal and professional successes and struggles. And this lack of a singular, simple narrative arc is, according to many, a detriment to her campaign.

Political storytelling isn’t about policy, credibility, or qualification — Clinton can discuss those all day. People connect with candidates, McKinnon says, the same way they connect with books and movies; they simply won’t engage without a good story.

As political hopefuls have begun to realize this, they’ve infused their campaigns with more and more storytelling. In the mid-90s, Bill Clinton’s narrative was economic growth. In the 2000’s, George W. Bush’s was protection for the American people. Obama’s campaign was built on a story of hope and change.

So has the narrative language that’s so crucial to selling the candidate trickled down into the politicians’ speech?

Are our presidents using more storytelling language in their individual communications than their predecessors? What about our current presidential hopefuls? Are their strong narrative foundations (or lack thereof) reflected in their campaign communications?

We analyzed every State of the Union Address from John F. Kennedy through Barack Obama to find out whether we could see the storytelling trend taking shape in the recent political landscape, and we analyzed Clinton’s and Trump’s performance throughout the primary debates to see whether their stories are reflected in their language.

The answer, in both cases, is yes.

Despite a few outliers, the general trend in State of the Union Addresses has been toward an increase in storytelling language—there’s been a twofold increase during the last 55 years.

President Obama, whose reputation as an excellent speaker predates his stay in the White House, is also attuned to the importance of storytelling. In a 2012 interview, the president said his biggest mistake during his first few years in office was not telling enough stories.

“The nature of this office is also to tell a story to the American people, that gives them a sense of unity and purpose and optimism, especially during tough times. […] In my first two years I think the notion was, “Well, he’s been juggling and managing a lot of stuff, but where’s the story that tells us where he’s going?” And I think that was a legitimate criticism.”

Again, we were curious. So we took a look at each of the eight State of the Union Addresses Obama has given during his two terms in office, and we found that the president has taken those criticisms to heart. His use of storytelling language increased by 27% between his first SOTU and his last.

President Obama’s final State of the Union used more storytelling language than any other SOTU we analyzed.

What does storytelling language look like?

Storytelling language gives a speech — or a letter or an annual report — the qualitative elements that help audiences engage with the speaker and recall the key points. It’s what enables us to relay the message to our coworkers or our friends and family, long after hearing it.

We gauge storytelling language on a wide variety of components, identified through years of communication research. These include emotional undertones, sensory words that evoke setting, and the anxiety-building language that makes us want to keep listening for a resolution. To measure storytelling, we identify the frequency with which a speaker uses these and other key storytelling traits, then establish a score — a percentage, scaled 0-100 — that indicates how much storytelling language a speaker uses compared to all other communications in our database of over 100,000 spoken and written samples.

President Obama’s final State of the Union is an excellent example. His strength in that address is in creating small narrative arcs to drive the speech — outlining the obstacles and challenges, the path of progress, and the sense of unified achievement that make a story worth retelling.

“Each time, there have been those who told us to fear the future; who claimed we could slam the brakes on change, promising to restore past glory if we just got some group or idea that was threatening America under control. And each time, we overcame those fears. We did not, in the words of Lincoln, adhere to the dogmas of the quiet past. Instead we thought anew, and acted anew. We made change work for us, always extending America’s promise outward, to the next frontier, to more and more people. And because we did — because we saw opportunity where others saw only peril — we emerged stronger and better than before.”

So what does that mean for the 2016 election?

We won’t begin to try to predict the outcome of the 2016 election — we’ll leave that to Nate Silver. What we can do — and did do — is analyze the language Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump used in every single primary debate to find out who’s telling more stories.

Throughout the primary debates the two candidates participated in, both used far more storytelling language than the average politician.

However, Trump used, on the whole, nearly 30% more storytelling than Clinton.

While Trump’s use of storytelling hovered in the high 90th percentile throughout the primaries, Clinton’s was not as steady. During the last two democratic debates, Clinton’s storytelling language increased significantly, narrowing the gap between her speech and her opponent’s. A sign that she’s shifting her communication strategy?

The analysis matches our intuition. Regardless of either candidate’s political position or qualifications for office, Trump’s story has been clear and consistent throughout his campaign, while Clinton’s has been harder to pin down.

It’s anybody’s guess as to what will happen as the general election progresses. But you can be sure we’ll be tracking the stories.